The Cayman Islands transformed from a seafaring economy in the 1950s into one of the world’s leading offshore financial centres through political stability, modern commercial laws, and sustained international investment. Today, Cayman combines sophisticated legal and financial services markets, global work, and long-term professional opportunities for lawyers considering offshore careers.

--------------------------------------

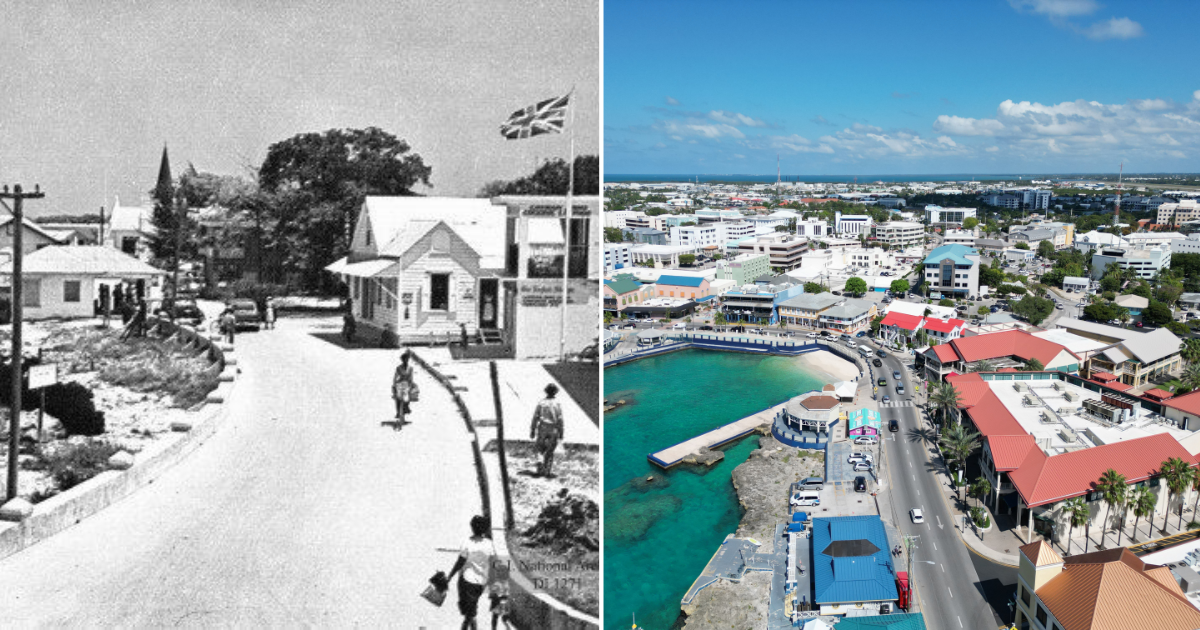

Only 60 years ago, the Cayman Islands were an isolated maritime community relying on turtle fishing, small-scale shipbuilding and subsistence agriculture to sustain its small population. In present day, the picture could not be more different. By 2023, financial services accounted for 44% of GDP, generating USD$2.5 billion in economic activity and positioning Cayman as one of the world’s most sophisticated offshore financial centres.

In 1950, the Cayman Islands were a very different place from the global financial centre we know today. In fact, there were no banks at all - not on Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac, or Little Cayman.

Daily life reflected this modest economic base. There was only one paved road in Grand Cayman, no telephones, and no large-scale businesses. Most Caymanian families lived by arduous, resourceful means living season to season, dependent on the reliability of the sea.

On land, Caymanian families practiced subsistence agriculture and traditional crafts to get by. Arable land was limited and soils thin, so farming was mostly small-scale. Most families could only grow enough food to support themselves. Common crops included breadkind root vegetables like cassava, yam and sweet potatoes, along with plantains and corn.

Many families raised a few chickens, goats or a cow for eggs, meat, and milk. Some staples like rice, flour and sugar had to be imported (usually from Jamaica) when available.

Another vital home industry was making rope and thatch products from the endemic silver thatch palm. Caymanian women (and men) harvested palm leaves to braid thatch rope, prized for its durability in saltwater. This rope, along with woven thatch hats and baskets, was one of the few exportable products and could be traded abroad for necessities.

Overall, cash was scarce in the 1940s–50s Cayman economy. Many transactions were by barter or credit; for example, a seaman’s family might trade rope or homegrown produce at the local store in exchange for imported goods, with payment settled when the next remittance or turtle catch came in.

By the late 1950s, the foundations of this way of life were beginning to fracture. The introduction of larger bulk-cargo vessels sharply reduced demand for Caymanian crews, and the collapse of the Nicaraguan turtle fishery and introduction of plastic removed another long-standing economic lifeline for the islands. By 1965, the turtle industry brought in only £2,240 in exports.

Economically, the islands were vulnerable.

Politically, the region was changing even faster.

Across the Caribbean, British colonies were pushing for self-government. Jamaica, which administered Cayman as a dependency, was moving quickly towards independence. With fewer jobs, a shrinking traditional economy, and almost no cash economy, it was clear the islands were not prepared to stand on their own.

The resulting political uncertainty prompted the creation of a new Caymanian constitution, introducing elected representation and enabling the jurisdiction to begin shaping its own legislative future.

By the end of the 1950s, Cayman faced a daunting question: What would the islands become if the old economy could no longer sustain them?

The early 1960s represented Cayman’s first major pivot toward financial services. One of the earliest steps was the Companies Law (1960) which made incorporation in the Cayman Islands cheaper, faster, and locally controlled, replacing the old requirement to register companies through Jamaica.

In 1962, Jamaica became independent, but the Cayman Islands chose to become a British Crown Colony. This preserved access to English common law, ensured long-term political stability, and gave global investors confidence in the jurisdiction’s governance.

Cayman’s political system also became more representative: in 1961, Annie Huldah Bodden became the first woman appointed to the Legislative Assembly, underscoring the jurisdiction’s shift toward a more inclusive and stable political environment.

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1970s, Cayman’s elected representatives consistently prioritised collaboration over partisanship. While other Caribbean territories moved toward polarised party structures, often tied to ideological or racial identities, Caymanian leaders repeatedly rejected such pressures. This culture of consensus contributed significantly to Cayman’s later appeal as a stable financial centre.

Yet Cayman still lacked a financial industry.

This changed when the likes of William Walker and James Macdonald arrived. Both were lawyers educated abroad at top institutions, connected to international networks and were skilled in corporate and trust law.

Macdonald arrived first, in 1960, initially just to attend proceedings of the Legislative Assembly. However, he soon became a Cayman resident and began promoting the jurisdiction’s emerging tax advantages. Walker, born in British Guiana and educated in Barbados and later at Cambridge University, arrived in 1964 after practising law in Canada.

Together, they became central figures in drafting the Banks and Trust Companies Regulation Law (1966) and Trusts Law (1966). These laws aligned Cayman with the rapidly expanding Eurodollar markets and created the legal infrastructure needed for international finance.

Walker and MacDonald’s law firms would later transform into major players on the global financial stage. William S. Walker’s firm, W.S. Walker & Company (founded in 1964), eventually grew into the international law firm now known as Walkers. Likewise, Canadian attorney James MacDonald partnered with Cambridge-educated lawyer John Maples in the mid-1960s to establish the firm MacDonald & Maples. In 1969, Maples’ Cambridge classmate Douglas Calder joined the partnership, prompting a renaming of the firm to Maples and Calder (now known simply as the Maples Group). Both Walkers and the Maples Group have since become recognised as two of the largest offshore law firms in the world.

Another key figure in shaping Cayman’s early financial industry was Caymanian Sir Vassel Johnson, the jurisdiction’s first Financial Secretary (1965–1982). Johnson played a central role in establishing the policy, regulatory and institutional foundations that allowed the new financial services sector to scale. Under his leadership, Cayman enacted several landmark pieces of legislation all of which gave the jurisdiction a robust, business-friendly legal framework aligned with the rapidly expanding international markets.

Johnson also championed a model of close public–private collaboration that became a defining characteristic of Cayman’s development. He later oversaw key institutional reforms, including the creation of the Cayman Islands Currency Board in 1971 and the introduction of the Cayman Islands dollar. His steady leadership and clear vision were widely credited with helping transform Cayman from a small maritime economy into an internationally respected financial centre.

By the mid-1960s, Nova Scotia Trust Company and Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) had opened branches, signalling to the international financial community that the jurisdiction had potential. These early entrants were not accidents. They came in direct response to the legislative environment crafted by Walker and Macdonald.

During the 1960s, The Bahamas emerged as a leading offshore financial centre, an archetypal tax haven that attracted hundreds of foreign banks and trust companies to Nassau with its zero-tax regime and investor-friendly laws. As the decade ended, the political uncertainty in the Bahamas around independence created unease in the international financial community. Wealth managers, banks and corporate clients began searching for a stable alternative in the Caribbean. The Cayman Islands were British, stable, legislatively modern and therefore well placed for expansion.

For decades, the Cayman Islands relied on the Jamaican dollar as its official currency. In 1972, however, the territory took a decisive step toward greater financial autonomy by introducing its own currency: the Cayman Islands dollar. Two years later, in 1974, the new Cayman dollar was officially pegged to the U.S. dollar, a move reflecting the islands’ growing economy and desire for a stable currency. The creation of this currency strengthened the Cayman Islands’ monetary credibility and reassured international investors of its long-term stability.

As this monetary foundation was established, global financial conditions were shifting. The Eurodollar market was expanding, onshore regulatory environments were tightening, and regional uncertainty encouraged financial institutions to look for stable, well-governed jurisdictions.

These factors set the stage for Cayman’s first era of large-scale international bank growth. Institutions from Canada, the United States and Europe began establishing operations at a rapid pace. By the end of 1976, more than 126 banks were licensed in the jurisdiction, collectively holding over USD $21.9 billion in assets.

Another significant development was the introduction of the Confidential Relationships (Preservation) Law (CRPL) in 1975. The law codified the English common law duty of confidentiality and provided statutory clarity for banks, lawyers and trust companies, reassuring international clients that their information would be properly protected.

The decade concluded with the introduction of the Insurance Law of 1979, which created a framework for captive insurance companies. This allowed multinational corporations to establish insurance structures in Cayman at a time when many were seeking to diversify their risk jurisdictions.

By the end of the 1970s, the Cayman Islands had moved far beyond their modest economic foundations. With a stable currency, a rapidly growing banking sector, established legal protections, and a newly emerging insurance industry, the jurisdiction had laid the pillars of what would become one of the world’s most sophisticated offshore financial centres.

The 1980s brought heightened US scrutiny of offshore financial centres. The Cayman Islands responded by cooperating with US authorities, signing the Narcotics Agreement in 1984 which allowed sharing of information with US authorities for drug-related investigations on a controlled, case-by-case basis.

This later evolved into the broader 1986 Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT), which established clear legal procedures for providing evidence such as banking and corporate records. This rules-based cooperation helped differentiate Cayman from less transparent jurisdictions and reinforced its reputation as a credible, well-regulated financial centre.

By the end of 1986, Cayman hosted 16,791 registered companies, 456 banks and trust companies with US$202 billion in assets, and more than 100 captive insurance companies.

The 1990s cemented Cayman’s position as a global financial centre. The Mutual Funds Law (1993), now known as the Mutual Funds Act, established a clear regulatory architecture for the rapidly growing investment funds industry – now one of the key sectors in the jurisdiction. Amendments to the Trusts Law and company regulations ensured that Cayman remained competitive, flexible, and aligned with international best practices.

The growth was extraordinary: by the end of 1996, the jurisdiction was home to 37,919 registered companies, 575 banks and trust companies with assets of US$507.8 billion, 378 captive insurers, and nearly 1,400 mutual funds.

At the end of the decade, the Cayman Islands had become one of the world’s most sophisticated offshore financial centres. This rapid expansion created sustained demand for offshore legal expertise, private client work, fund formation, corporate transactions and restructuring.

As Cayman entered the 2000s, its financial services sector was no longer emerging, but a major global player and with scale came international scrutiny.

In 2000, the FATF added Cayman to its list of non-cooperative jurisdictions based on perceived deficiencies in information. The jurisdiction responded with an unprecedented pace of reform and within a year, it was removed from the list.

At the same time, Cayman agreed to deepen its cooperation with the international tax community signing the Tax Information Exchange Agreement (TIEA) with the United States. While also negotiating favourable treatment under the EU Savings Directive (EUSD) that kept its investment funds outside the scope of an EU tax reporting rule, helping preserve the jurisdiction’s appeal to global investors.

Building on earlier legislation which strengthened its AML framework, the jurisdiction also established the Cayman Islands Monetary Authority (CIMA), which became fully operationally independent in 2002. CIMA quickly became the anchor of the modern regulatory system, responsible for banking, funds, insurance, and the rapidly expanding investment sector.

By the end of 2001, the scale of Cayman’s financial sector was unmistakable. The jurisdiction was home to 64,495 registered companies, 427 banks with assets exceeding US$800 billion, 3,648 mutual funds, 542 captive insurance companies, and 418 listed securities on the CSX.

A crucial component of Cayman’s rise as a stable and sophisticated financial centre has been the strength of its judicial system. While Cayman inherited English common law traditions from the outset, its modern commercial judiciary was significantly reinforced with the creation of the Financial Services Division of the Grand Court (FSD) in 2009.

The FSD was established in recognition of the growing complexity of cross-border litigation, insolvency, restructuring, and trust disputes arising from Cayman’s financial services sector. Its dedicated judges, specialist procedures, and ability to allocate judicial resources quickly have made it one of the most respected commercial courts in the offshore world.

For investors, fund managers and multinational institutions, the presence of a predictable, highly skilled and well-resourced court is one of Cayman’s most important advantages. For lawyers, it offers exposure to international advocacy, complex commercial litigation and appellate work that rivals major onshore centres.

By 2010, Cayman had not only weathered global scrutiny, but it had also emerged stronger, more trusted, and more strategically positioned than at any point in its history.

Beginning in 2013, the Cayman Islands implemented major tax-transparency frameworks, including FATCA with the United States, a parallel agreement with the United Kingdom, and the OECD’s Common Reporting Standard. This shift was followed by the International Tax Co-operation (Economic Substance) Act, which came into force on 1 January 2019 and required relevant entities to demonstrate real economic activity in the Islands rather than merely holding a registered presence. In 2019, the OECD reviewed Cayman’s implementation of these measures and confirmed that it met international standards.

Regulatory capacity also expanded significantly. Between 2017 and 2020, CIMA strengthened its supervisory function by hiring more than 50 AML/CFT specialists, improving its ability to detect and prevent financial crime. In 2020, the Private Funds Act introduced regulation for closed-ended funds for the first time, bringing thousands of vehicles into routine audit, valuation and reporting requirements.

By the mid-2020s, Cayman’s financial services sector has grown to a scale few could have predicted a generation earlier. The investment funds industry continues to dominate globally, with 30,860 funds domiciled in the Cayman Islands as of October 2025. Corporate registrations also remained strong, with 122,700 active companies recorded by June 2025, underscoring the jurisdiction’s ongoing appeal as a stable, well-regulated and internationally connected financial centre. The jurisdiction is also home to 229 fintech companies, including 11 with Series A financing and three that have reached unicorn status with valuations exceeding US$1 billion.

For lawyers considering a move offshore, understanding Cayman’s trajectory is not merely academic, it explains why the jurisdiction offers some of the most sophisticated and stable legal work available today.

Cayman’s rise was not accidental. It was the result of deliberate legislative choices, political stability, international cooperation and decades of sustained investment in legal and financial infrastructure.

Today, lawyers in the Cayman Islands gain exposure to complex cross-border transactions, major global clients, large-scale disputes, fund formation, finance and restructuring work, often much earlier in their careers than onshore.

The jurisdiction’s stability also supports career longevity: predictable legislation, strong judiciary, high-quality infrastructure and a deeply international professional community.

Cayman’s past explains its present and its present points to a future full of opportunities for ambitious legal professionals.

--------------------------------------

Whether you’re exploring roles with leading offshore law firms in the Cayman Islands or Bermuda or seeking tailored relocation advice, our team is here to help.

Still deciding between offshore jurisdictions? Compare the Cayman Islands, Channel Islands, BVI and Bermuda to see which is the best fit for you.

--------------------------------------

Bank for International Settlements (2007). The Cayman Islands and the Global Financial System. Available here.

Cayman Compass (17 November 2008). Sir Vassel Remembered. Available here.

Cayman Compass (2025). New Report Reveals Growing Economic Impact of Cayman’s Financial Services Industry. Available here.

Cayman Islands Government Office UK (October 2018). A Brief History of the Cayman Islands (e-book). Available here.

Cayman Resident (18 September 2025). Establishing a Business in the Cayman Islands. Available here.

Freyer, T. & Morriss, A. (2013). Creating Cayman: The Institutional Foundations of a Financial Centre. George Mason University School of Law. Available here.

Funds Europe (2025). Why the number of private funds in the Cayman Islands has surged 40% in five years. Available here.

International Monetary Fund (2009). Cayman Islands: Assessment of Financial Sector Supervision and Regulation. Available here.

Judicial Administration of the Cayman Islands (n.d.). Financial Services Division – Structure of the Courts. Available here.

Mourant (2023). Investment Funds in the Cayman Islands – A Guide. Available here.

Stuarts Walker Hersant Humphries (2022). Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI) Obligations for Cayman Islands Entities. Available here.

The Legal 500 (2025). Cayman Islands: Fintech. Available here.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (1998). Financial Havens, Banking Secrecy and Money Laundering. Available here.